It's a bear!

Los Angeles Era Bb-F-E Bass Trombones

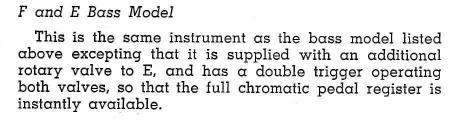

The unavailability of the B below the bass clef staff has been an issue with the Bb-F single rotor "tenor-bass" trombone for as long as such instruments have been made. Since extended positions were necessary due to the added length of the horn with the f attachment engaged, the handslide just wasn't long enough (the extended sixth position necessary for the low C being at or near the end of the slide). One could just put the slide out all the way and lip the pitch down, but it's very difficult to match the timbre of the other notes. Extending the attachment to an E brought the B within marginal reach, but compromised the usefulness of the the valve for other purposes. The obvious solution was to design an attachment that was normally in F, but could be changed to E when needed, so manufacturers added either a long-pull crook or a static valve (stillenventil) in attachment's tuning slide for the E extension. The drawback to either of these solutions was that the trombonist had to stop playing and bring the horn down to either pull a crook or turn a valve when changing between the F and E tunings. There also remained the question of a few pieces in the repertoire that require a glissando between the low B and the F at the bottom of the bass clef staff; if the attachment was tuned to E, the only place to play F was in sixth position, so executing a smooth glissando was a challenge for even the best players.One final step was necessary to realize a bass trombone that was truly chromatic in a fully-functional way.

Enter Reynolds (working with Allen Ostrander of the New York Philharmonic and Kauko Kahila of the Boston Symphony) and Holton (working with Edward Kleinhammer of the Chicago Symphony). In the late 1950's, both companies developed bass trombones with a second rotor and controls that allow that second valve to be engaged and disengaged while playing. There has alway been some debate as to where and with whom the idea originated (this is discussed on Doug Yeo's website here and referenced on Contempora Corner here and here), and whether the installation of Holton's non-integral second valve really constituted a "double", but Holton and Reynolds have generally shared the credit for the innovation.

Then, a few years ago, Robb Stewart ran across this entry in a pre-WWII Olds catalog:

When I heard about this, I started looking for an example of the horn that went with the catalog listing.. I knew it was unlikely that many were built (bass trombones were not in as wide a use then as today), but I was certain that they wouldn't have put it in the catalog if they hadn't built at least one.

Since then, I've documented four doubles built during Olds' Los Angeles era (which ended when the move to Fullerton was completed in 1955). Three date from the late 1940's - the two in my possesion (shown below) and a third, s/n 31013, which sold on eBay in July, 2012. The fourth, and most significant, was located by Dr. Jon Moyer, a music teacher in south central Pennsylvania, and is also in my collection. Its serial number (132xx) dates it to approximately the same time as Robb Stewart's catalog - roughly twenty years prior to the appearance of the Holton and Reynolds doubles.

I also now have a CMI/Olds advertisment from February, 1941 that includes a photograph showing a simlar horn.

Did Ostrander, Kahila, or Kleinhammer know of the existence of these horns? I think it highly unlikely, for several reasons. For one thing, Olds wasn't a factor in the symphony trombone market. For another, any sort of bass trombone was a low-demand item back then - Olds wouldn't have aggressively marketed it, nor is it likely that Olds' largest distributor, Chicago Musical Instruments, made any effort. One also has to consider the issue of regional isolation; in an era when many people still travelled by rail, Los Angeles was a two-day train ride from Chicago and three days from New York or Boston. I should also point out that, to the best of my knowledge, none of the four examples mentioned were used for symphony orchestra work.

c. 1941 Olds Bb-F-E Bass Trombone (George A. Roye)

Bore: .530"-.554" (13.5 mm-14.1 mm), .585" (14.9 mm) attachment

Bell: 9" (228.6 mm)

I'his instrument first came to my attention back in 2011. Dr. John Moyer, the tromboninst and music teacher in the York, Pennsylvania area, had contacted Robb Stewart and Robb had referred him to me. Dr. Moyer found this horn in a storage area belonging to the Spring Garden Band in York, Pennsylvania. The story he was given was that it had belonged to a former band member, George A. Roye (1921-1965). Mr. Roye worked as a professional trombonist in the immediate post-WWII era, including stints with the Cole Brothers Circus and the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus. Around 1950, he settled in Columbia, Pennsylvania and married Lilian Wittmack (or Wittmaack), a well-known Danish-born equestrian performer (I can't find anything specifically saying so, but it's reasonable to conclude that George and Lilian met while both were performing with Ringling Brothers during the 1949 season). They established an equestrian center (Bri-Mar Stables) in 1951. George became an "industrailist" (to quote one news article), but continued to play with local groups, including the Spring Garden Band; he passed away in 1965 and this horn was apparently left behind at the Spring Garden Band facility. Unfortunately, Dr. Moyer was not able to find out when or where George Roye purchased this instrument, so it's not likely that we will ever know if he was the original owner or if he acquired it second-hand. I do not think that he would have used it for circus work; it's a heavy horn with a heavy slide and dubious ergonomics and would not have been suitable for long days playing programs heavy on screamers and gallops.

At first glance, this instrument appears to be the same design as the later Olds dependent doubles shown below, but closer examination reveals several significant differences. The slide has a smaller bore (.530"/.554" vs. .554"/.565") and the slide is narrower, with a curved third brace - reminiscent of the slide of the earlier Standard Symphony, but a bit wider (in fact, the tenon joint components on this horn match up to the Symphony model and are a smaller than those on later doubles). The mouthpiece receiver is also smaller; it's actually slightly undersize for a medium-shank mouthpiece. As for the bell, it has a 9" flare, but (based on mute insertion depth) the throat is actually a bit larger than the late 1940's horns.

Overall View |

Valves |

Slide Braces and TIS Mechanism |

Overall View Back |

Engraving |

End Crook (no ferrules) |

c. 1947 Olds Standard Bb-F-E Bass Trombone

Bore: .554"-.565" (14.1-14.4 mm), .585" (14.9 mm) attachment

Bell: 9" (228.6 mm)

I purchased this horn through eBay from a band director in Phoenix, Arizona. He said that he bought it in about 1991 from a man who had played it in the Artie Shaw Orchestra, but he didn't remember the man's name (the seller was only twelve years old at the time). He had played it up though his second year of college before his trombone teacher had strongly suggested that he get a newer horn. The serial number is in the low 20,000's, which dates it to approximately 1947. The accompanying mouthpiece is unmarked, but its design is consistent with Olds mouthpieces of the era. The mouthpiece receiver is significantly smaller than those on newer (1960's & 1970's) Olds basses in my collection (which are already about .010" undersize compared to their non-Olds contemporaries). One feature possibly unique to this instrument is the location of the pivot for the F-E attachment levers. On earlier and later versions, the pivot is attached to the neckpipe; on this horn, it is attached to the bell brace. This configuration places the levers such that they are easier to reach, but also prevents the player from tucking his/her thumb in under the lever. For a trombonist who did a lot of playing in the trigger register, this would have probably been an improvement, but it would have made the horn less confortable for someone who only used the valves occasionally.

The other Olds bass trombones of this general design (both singles and doubles) that I've seen are only marked "The Olds", but this one is marked "The Olds Standard". The Standard name first appeared in the mid-late 1920's; when Olds introduced their Self-Balancing model, the older TIS design became the Standard model. That original Standard was identified as such in sales literature and the like, but (to the best of my knowledge) the instruments themselves never actually carried the name. During the era when this horn was made, Olds was producing a different Standard model - a bell-tuning design that was a continuation of the Self-Balancing and a precursor to the Special and Studio. The engraving on that later Standard does include the model name, and this instrument carries that engraving, making this one of the few TIS Olds trombones (if not the only one) actually marked as a Standard.

Overall View |

Valves Front |

Valves Back |

Slide Braces and TIS Mechanism |

Engraving |

End Crook (no ferrules) |

c. 1949 Olds Bb-F-E Bass Trombone

Bore: .554"-.565" (14.1-14.4 mm), .585" (14.9 mm) attachment

Bell: 9" (228.6 mm)

This instrument came to me through eBay from a man living in the Mid-Wilshire district of Los Angeles, only a couple miles from the location of the factory where it was built. The serial number is in the low 30,000's, making a couple years newer than the one shown above. The horn, along with the accompany accessories, paints a picture of a trombonist who put significant effort into refining his equipment. Some of the clues:

- 9" bells were the norm for Olds basses; the 9½" bell would have had to be made to order.

- A piece of nickel silver sheet has been added to the f valve, apparently to prevent the player's collar from coming in contact with the valve. It's very well integrated into the horn, so it was probably installed by the factory.

- The horn has a movable handrest attached to the main bell brace; based on my trials, this handrest is supposed to rest in the player's palm and place his hand in a better position for actuating the valve levers.

- The heavy, custom double case; as can be seen from the pictures, a small-bore Olds tenor (in this instance, a pre-WWII Super) fits perfectly.

- The four mouthpieces that came with the horn, two of which were custom-made by Olds (more on that below).

- There is a D crook; it is quite old, but possibly not as old as the horn. The brace is a close match to those on the main horn, but is made of nickel, while the others appear to be brass.

The mouthpieces:

Roe Plimpton was Olds' mouthpiece maker, so he most likely made both of these. "J-J" and "Jamison" would refer to the owner. I was able to find one reference to a trombonist name Jim Jamison, who was active at the time when this horn was built. I also spoke with Robby Robinson, a long-time LA pro; he told me that Jim Jamison was bass trombonist in the studios.

Plimpton/Jamison |

Plimpton/Jamison |

Plimpton/Jamison |

Olds/J-J |

Olds/J-J |